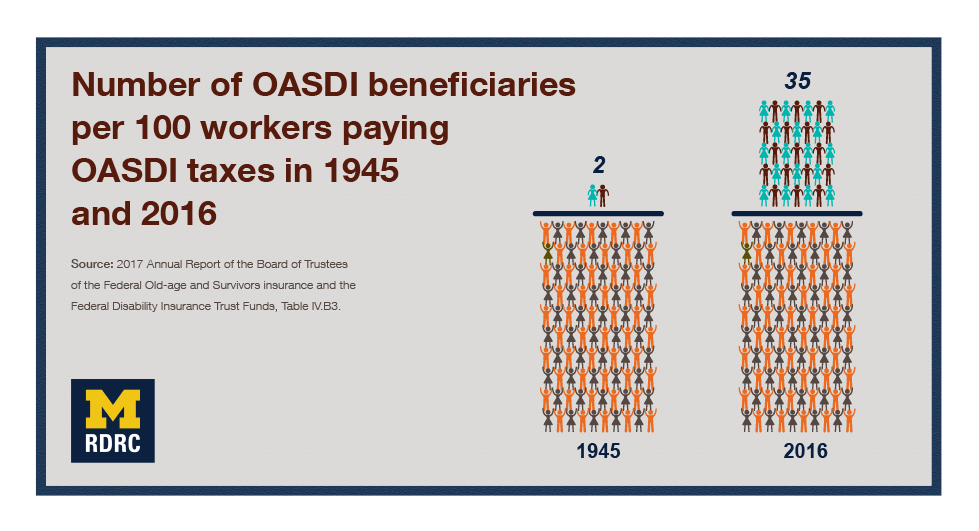

How to fix the solvency issues of the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) trust funds, often referred to as the Social Security trust funds (OASDI), continues to concern policymakers and voters alike. As a pay-as-you-go system, payroll taxes collected from today’s workers and their employers fund current beneficiaries’ OASDI payments. When today’s covered workers retire, their benefits will be paid by the next generation of OASDI taxpayers. In 1945, there were two beneficiaries for every 100 covered workers. In 2016, there were 35 beneficiaries per 100 covered workers. [1] Declining numbers of births, more years spent in retirement due to longer lives, and fewer people ages 25 to 54 working have played roles in the rise of that ratio. Understanding these trends is important for everyone concerned about the OASDI trust funds’ health.

In this three-part blog post, we look at recent MRDRC research surrounding demographic and labor participation changes and how those changes might intersect with potential policy reforms.

First: labor force participation.

The decline of the labor force participation rate (LFPR) has played a role in the rising ratio of OASDI beneficiaries to workers. The LFPR indicates the fraction of the U.S. population 16 and older who are working or looking for work and are not active duty members of the armed forces or living in institutions such as nursing homes. Fewer people participating in the workforce — a lower LFPR — mean fewer OASDI taxes collected. The LFPR directly affects the ratio of OASDI beneficiaries to workers. Understanding who doesn’t participate and why (disability, educational pursuit, slow wage growth) might help determine whether we need policies to encourage work, and if so, what the policies might look like.

The LFPR peaked in 2000 at 67.3 percent and has hovered around 63 percent for the last two years. Many theories exist as to why fewer people are working. Researchers Francisco Perez-Arce, Maria J. Prados, and Tarra Kohli recently completed a review of published and unpublished studies that explore the causes of LFPR decline. Altogether, the literature found that cyclical reasons (for example, unemployment due to the Great Recession) didn’t explain the decrease, but demographic trends such as population aging could account for about half of the decline. Other findings the authors consistently saw in the literature:

- Social and welfare programs, such as changes in Social Security retirement benefit claiming and disability insurance rules, affect the LFPR, but differently according to which group is studied.

- There is no broad agreement on the effects of technological progress (such as automation/robots), the opioid crisis, or worldwide trade on the LFPR.

- The literature doesn’t have much to say on the behaviors of women and young men ages 25 to 54. Some potential factors in their decreased LFPR are leisure-enhancing technologies (for example, video games), increased school enrollment, or low-wages for less-skilled workers.

In his 2018 working paper, Ananth Seshadri finds that roughly half of the LFPR decline is due to demographic changes, confirming what Perez-Arce and company found in their literature review. To track how and why different groups go into and out of the work force, Seshadri uses data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID). Unlike the CPS, the PSID tracks respondents over time and asks more detailed questions about work history and health. He also looks at wage data to assess how labor supply/demand effects LFPR.

Since each potential reason for not working would affect distinct age groups differently, Seshadri looks separately at those younger than 30, 30 to 44, 45 to 59, and 60 and older. Seshadri’s findings include

- Young workers in particular have been less likely to enter the labor force and more likely to leave.

- Across ages, disability seems to be an increasingly common factor limiting work.

- Between and across demographic groups, Seshadri finds signs that wages and labor force participation tend to move together. This supports the idea that slow wage growth might discourage workers from seeking employment. The link between wages and participation has been strengthening over time, suggesting those who are employed try to stay that way. Those who lose a job, on the other hand, have fewer reasons to return to work.

For more details, read Seshadri’s and Perez-Arce and co-authors’ working papers, which include the technical details of their studies.

[1] 2017 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-age and Survivors insurance and the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds, Table IV.B3.—Covered Workers and Beneficiaries, Calendar Years 1945-2095